Communication Cycle model by Shannon and Weaver

Communication Cycle model: this article explains the Communication Cycle model by Claude Elwood Shannon and Warren Weaver in a practical way. After reading you will understand the basics of this powerful communication tool.

What is the Communication Cycle?

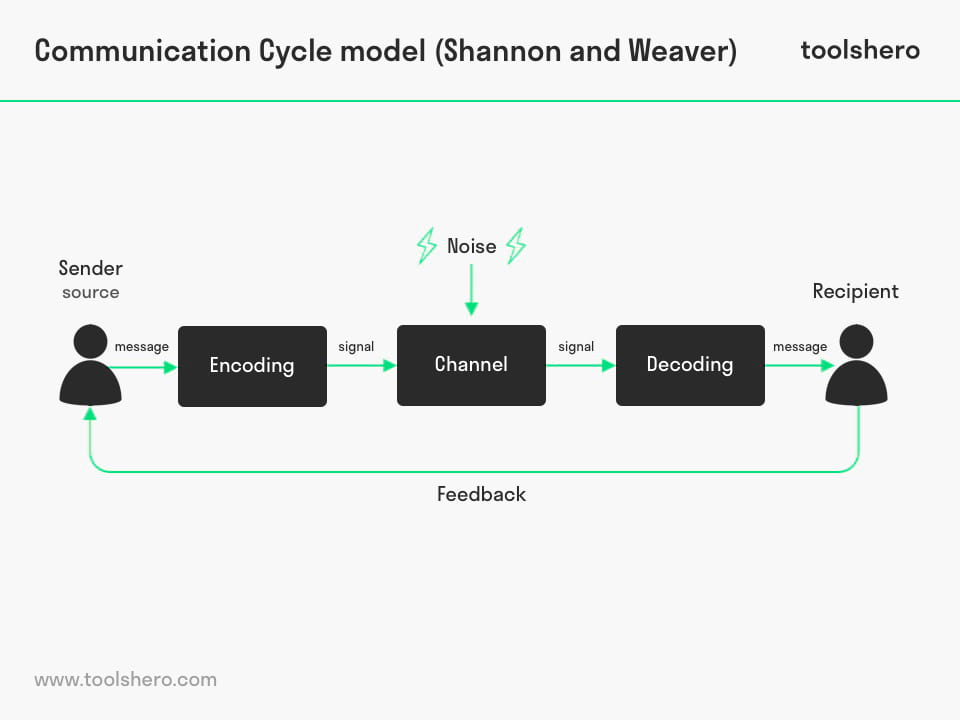

The Communication Cycle model is a linear model of communication that provides a schematic representation of the relation between sender, message, medium/ media and recipient. It was developed by Claude Elwood Shannon and Warren Weaver.

Communication is a very complex process that happens orally, in written form as well as in non-verbal form, and in which the message that is being sent, takes place in a certain context. Both the sender and the recipient can respond to each other in this model, with the sender and recipient alternating roles. This leads to a cyclical process.

Communication Cycle: sender, message and recipient

To really understand the Communication Cycle model, it’s wise to first take a closer look at all components. First, there’s the sender. He has an expressive function. Through language and/or body language, he expresses something and sends it to the recipient. It can be information, an emotion, song, dance, and so on.

The thing he sends, is the message. This message is intended for the recipient(s). How the recipient handles it and interprets the message is called the appellative function. The message itself has to be carried by a medium, also called a channel.

The sender usually uses multiple media to get to the recipient. In addition to the voice for spoken words, the sender uses gestures, facial expression, posture and intonation as media. He can also use supporting media, such as a PowerPoint presentation, flip chart, music or a slide show.

Coding and decoding the message

A message is communicated in different ways; spoken and written words (language), signs such as smoke, colours and symbols (semantics) and body language (non-verbal communication).

How the message is communicated and how it is understood are two different things. On the one hand we see (en)coding and on the other decoding. A message has to be transmitted in such a way that it can be understood by both the sender and the recipient.

For this, the sender uses coding. He translates what he has in his head to understandable language, with the intention that the recipient will understand what he means. He therefore carefully chooses his words, considers the level of his recipient and tries to make clear what he means. That’s why it’s good that a sender focuses on a target group and tailors his message as much as possible to that group.

Conversely, the recipient tries to ‘crack’ the sender’s message through decoding. He interprets what he’s seeing and hearing and translates it into thoughts. Because every human being has their own and unique frame of reference, determined by background, education, how they were raised, experiences and so on, every individual will interpret a message differently.

The more clearly the sender has encoded the message, the more accurately the recipient can decode it, minimising the chance of misunderstandings.

Noise

Still, there can be interference in the Communication Cycle that leads to misunderstandings. This is then referred to as miscommunication. Within communication, that kind of interference is called noise or static.

This noise can occur internally, within the Communication Cycle model, or externally, outside of the Communication Cycle model. When the interference is created on purpose, it is known as intentional noise.

Internal noise usually occurs at the sender or at the recipient. When the sender experiences internal static, he won’t be able encode his message accurately. The sender might be using too much specialist language (jargon) that won’t be understood by the recipient right away or the sender might encode a message that is full of prejudices and/or personal opinions. Speaking with a heavy accent or hoarse voice can also lead to the message not being communicated properly, meaning it’s not encoded properly.

The recipient can also experience internal noise, making it impossible for him to properly receive the message and decode it. For example, the recipient might be distracted or already have a certain preconception or opinion that prevent him from listening properly. Headaches or fatigue are other well-known forms of internal static on the side of the recipient.

The external noise generally happens outside of the sender and recipient. A bad phone connection, a flickering light, a hot exam classroom or construction noises are examples of this.

Sometimes it’s possible to reduce or remove the external noise, but that doesn’t always work. It can be the case that the static is generated intentionally, like turning up the music or nervously ticking on a table. That is referred to as intentional noise.

Feedback

As soon as the recipient responds to what the sender has sent, you get feedback. When the sender then responds to the recipient’s message, this is called a response.

Most of the time, the recipient’s feedback is given consciously.

But it can also be the case that he’s giving unconscious feedback through non-verbal communication. For instance, he can let the sender know that he has heard and understands the message by humming, but his raised eyebrows show that the opposite is true.

Subsequently, the sender can respond by asking a question for instance (‘I see that you don’t really get it, is that right?’) or by explaining it again in a different way (‘I’ll try to rephrase it’).

The sender’s response in the form of feedback is often a combination of verbal and non-verbal communication and causes the sender to be responsible for paying close attention to this.

Conventions

What is ‘normal’ for one person, is not always ‘normal’ to others. That depends on culture, and every country, city or village has its own conventions. Conventions are silent rules that we agree on together.

It also depends on the context in which the communication is taking place. On such example is the context of a warm day in August, when everyone is going to the beach. Nobody would think it’s strange when they see a father digging a hole with his son. And even when the son lies in the hole and the father buries him except for his head, hands and feet, nobody would look twice.

Together, we’ve ‘silently’ agreed that this is not a problem. However, things would be different if the context is still a warm day in August, but this is happening in a city park. It’s quite likely that a crowd would gather as soon as the father starts digging, and the police would probably intervene if the child lies down in the hole.

Together, we’ve agreed that this is a strange situation. The same would be true if the beach ritual would take place in winter or in the middle of the night.

When conventions aren’t clear for everyone, this can lead to noise, which can then eventually lead to misunderstandings and miscommunication.

Conclusion

Every step in the Communication Cycle model is essential, and it’s basically impossible to skip any of them. By paying attention to every component, both the sender and recipient are able to communicate effectively, understand each other better and react to each other more emphatically.

But it should be noted that it’s important for them to be open to each other, to ask questions, listen to and look at each other’s responses and adapting to each other. Only then can the quality of communication be continuously improved.

The Communication Cycle model is a functional means to communicate with each other, but also to communicate with public audiences.

By knowing in advance what the message is, how it will be worded (encoding), through which channels (media) it will be send to the recipient and what possible kinds of noise might occur, an organisation is able to purposefully start a conversation with its target groups.

It’s Your Turn

What do you think? How do you apply the Communication Cycle model by Claude Elwood Shannon and Warren Weaver in your business life? Do you recognize the practical explanation or do you have more additions? What are your success factors for getting your message across without creating misunderstandings?

Share your experience and knowledge in the comments box below.

More information

- Bowman, J. P., & Targowski, A. S. (1987). Modeling the communication process: The map is not the territory. The Journal of Business Communication (1973), 24(4), 21-34.

- Mcquail, D. & Windahl, S. (1995). Communication Models for the Study of Mass Communications. Routledge.

- Shannon, C.E. & Weaver, W (1971). The Mathematical Theory of Communication. The University of Illinois Press; First Edition (US) First Printing edition (1971).

- Wagner, E. D. (1994). In support of a functional definition of interaction. American Journal of Distance Education, 8(2), 6-29.

How to cite this article:

Mulder, P. (2016). Communication Cycle model by Shannon and Weaver. Retrieved [insert date] from Toolshero: https://www.toolshero.com/communication-methods/communication-cycle-shannon-weaver/

Published on: 22/09/2016 | Last update: 08/18/2022

Add a link to this page on your website:

<a href=”https://www.toolshero.com/communication-methods/communication-cycle-shannon-weaver/”>Toolshero.com: Communication Cycle model by Shannon & Weaver</a>

3 responses to “Communication Cycle model by Shannon and Weaver”

For me I still don’t understand how the theory of Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver is applied in business

communication. Please can you explain how this works?

This is a bit simplified version. I actually liked it. Thanks!

Here’s a response to Thomas’s question above, based on Patty’ outline of the Shannon-Weaver model above.

For business communication, here’s an example of a memo sent by a manager:

1. Sender: The manager writes the memo draft ready for emailing out.

2. Encoding: The computer encodes the memo draft into binary packets of data to be sent out to employees’ email addresses

3. Channel: The data is sent via cables that make up the word wide web, via email servers.

4. Noise: There may be misspelling in the memo (as Patty wrote above, that’d be internal noise), misinterpretation by the employees (internal noise), or the emails may end up in peoples’ junk mail boxes (external noise).

5. Decoding: The information in employees’ email inboxes is decoded via the computer and reconstructed in the same words as was originally written by the manager

6. Receiver: The employees receive the message.

7. Feedback: Some employees might write a reply email to the memo, asking for more clarification or providing their input.

Great article Patty!

Regards,

Chris