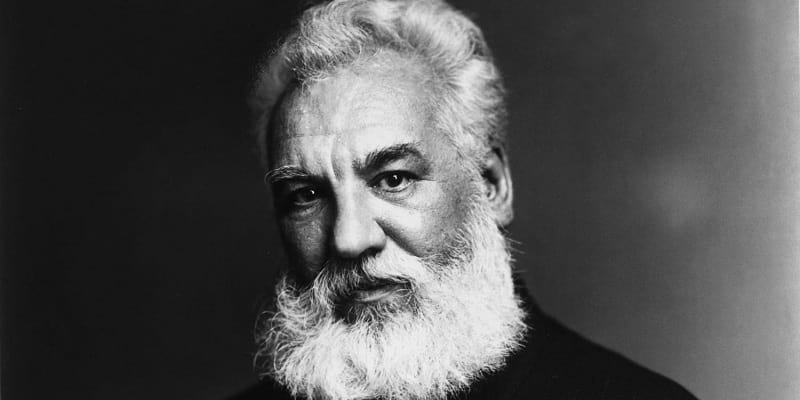

Alexander Graham Bell biography and quotes

Alexander Graham Bell (March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish inventor, scientist and engineer. Alexander Graham Bell is credited with inventing and patenting the first telephone. He was president of the Bell Telephone Company in 1877 and went on to be one of the founders of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T).

He did not only invent the telephone. Examples of other his inventions include the hydrofoils, optical telecommunications, and various aeronautical inventions. He was also the founder of early versions of the metal detector. Furthermore, he served as the second president of the National Geographic Society magazine from 1898 to 1903.

Who is Alexander Graham Bell? His biography

Alexander Graham Bell was born in Edinburgh, Scotland. The house in which he was born was on South Charlotte Street and today has an inscription honoring Hall’s birth. Alexander had two brothers: Melville James Bell and Edward Charles Bell. Both brothers would suffer from tuberculosis at a young age.

Father Alexander Melville Bell was a phonetician, mother Eliza Grace Bell a devoted stay-at-home mom. Alexander was given a name at birth: Alexander. When he was 10 years old, he asked his parents for a middle name, just like his brothers. That is why the name Graham was added to his name, after the name of a good friend of his father. To people close to Alexander he remained Aleck.

The family attended an area Presbyterian church during his childhood.

Childhood of Alexander Graham Bell

From an early age, Alexander Graham Bell showed great curiosity about the world. He collected botanical specimens and soon conducted several experiments. He often did this together with his childhood friend Ben Herdman, a boy from the neighbourhood.

Ben’s parents operated a flour mill. When Alexander was 12 years old, he built a device that combined the rotating paddles with a set of nail brushes. The result was a simple skinning machine, which was used in the mill. In return for this invention, Ben’s father, John Herdman, gave the boys a space in the mill’s workshop. Here the boys could continue to invent things.

Young Alexander Graham Bell had a sensitive character. He loved art, music and poetry. Without training for this, he learned to play the piano. He also enjoyed ventriloquism and constantly entertained relatives during visits. The boy was normally quiet and introspective and was saddened by his mother’s gradual deafness. He then learned a manual finger language, similar to sign language, which enabled him to have silent conversations with his mother.

He also devised a technique that allowed him to make modulated tones to his mother for her to distinguish. This would allow her to follow him with some clarity. His sadness gave way to fascination and the young Alexander Graham Bell later decided to study acoustics.

His father’s family were all reciters. His father published several pieces on the subject, many of which are still known today. An example of this is The Standard Elocutionist from 1860. In this manual, his father explains methods for teaching deaf-mutes to articulate words and read other people’s lip movements.

Visible Speech

Alexander Graham Bell also learned Visible Speech from his father. This is a way of identifying each symbol with its corresponding sound. He became so good at this that he gave demonstrations in public.

He became a true phenomenon and amazed many a spectator. He could decipher visible speech in virtually any speech, from Latin, to Scottish Gaelic and Sanskrit. He accurately recited written language without any knowledge of pronunciation.

Education and further inventions in the field of sound

Alexander Graham Bell, like his brothers, was homeschooled by his father. He was enrolled at the Royal High School in Edinburgh, but his schooling was marked by poor grades and absenteeism. He was particularly interested in the sciences, especially biology. He approached other subjects with great indifference, much to his father’s dismay.

After leaving school, young Alexander Graham Bell traveled to London to live with his grandfather, in Harrington Square. Here young Bell developed a close relationship with his grandfather. There were serious discussions and evening-long studies. It was during this period that Bell discovered his love of learning.

Bell’s father encouraged him to develop his interest in speech. He then took his sons to an automaton developed by Sir Charles Wheatstone, based on earlier work of Baron Wolfgang von Kempelen. This ‘mechanical man’ mimicked a human voice. The brothers then bought Von Kempelen’s book and built their own machine.

Father Bell was very interested in the project and encouraged the boys with the promise of a grand prize if they were successful. Alexander’s brother was concerned with the larynx and the throat of the machine, whilƒe Alexander worked on the more complex brain and skull of the automaton. Their efforts resulted in a lifelike head that could speak a few words.

Intrigued by the design, the boys continued to experiment. This time with a live subject, the family dog. Alexander Graham Bell taught the beast to growl and put his hand in the dog’s mouth to manipulate the lips and vocal cords.

He managed to get the dog to produce some sounds that somewhat resembled the sounds in the sentence “how are you grandma?”. These experiments prompted Alexander to take his interest in sound seriously, after which he began exploring resonance through the use of tuning forks.

Family tragedy

In 1865 the Bell family moved back to London. Alexander Graham Bell returned to Weston House as assistant teacher and worked on experiments with sound in his spare time.

He mainly focused on electricity to transmit sound. He installed a telegraph wire from his room at Somerset College to a room belonging to his friend.

The following year he attended the University of Edinburgh and later graduated from the University College of London. At the end of 1867, Alexander Bell fell ill, but not like his brother Edward.

As Alexander recovered, his brother grew sicker and sicker. Edward died. After his death, Alexander moved back home. His older brother Melville had married and was living elsewhere.

Alexander Graham Bell helped his father by giving lectures and demonstrations on visible speech. His first students were two deaf-mute girls who made visible progress thanks to Alexander’s efforts.

In May 1870, his brother Melville also died from complications of tuberculosis. A true family drama. Alexander also fell ill again, but recovered. He reluctantly entered into a relationship with Marie Eccleston, who was unwilling to leave England with him.

The now 23-year-old Alexander Graham Bell then traveled to Canada, together with his parents and his brother’s widow, Caroline Margaret Ottaway.

Here the party stayed with Thomas Henderson, a minister and family friend. The family soon bought their own piece of land with a farm. The lot contained an orchard, farm, piggery, chicken coop, and carriage house, adjacent to the Grand River.

On this plot, Alexander set up his own workshop. He did this in the converted coach house. Despite his weakened health upon arrival in Canada, Alexander quickly recovered and became happy again.

He continued to take an interest in the study of the human voice and found that it could also describe the Mohawk language in Visible Speech. For his contributions, he received the title of Honorary Chief and took part in the ceremony where he wore the headdress of the tribe. He danced traditional dances and received an honorary position in the group.

Working with deaf people

In the 1870s, Alexander Graham Bell devoted himself primarily to deaf people by training them in Visible Speech. He traveled to Boston, United States, and proved successful in training instructors.

He was then asked to do the same at several other institutions, including the American Asylum for Deaf-mutes and the Clarke School for the Deaf in Northampton.

Throughout his life, Bell tried to integrate the deaf and hard of hearing into the world of hearing people. He encouraged speech therapy and lip-reading over sign language.

Further experiments

In addition to his work with deaf people, Alexander Graham Bell continued to be interested in experimenting with sound. He became a professor of vocal physiology at Boston University of Oratory. Here he was carried away by the excitement that arose among scientists and inventors living in the city. He continued his researches and experiments, trying to discover a way to transfer musical notes and speech between mediums.

Although very interested, he found it difficult to devote enough time to his experiments. Due to ailing health, he decided to return to Boston in 1873. Here he decided to fully focus on his experiments with sound.

He set up a private practice in Boston and had only two students: Georgie Sanders, age 6, and Mabel Hubbard, age 15. These students would play an important role in his experiments. George’s father, Thomas Hubbard, was a wealthy businessman. He offered Bell a place to stay near Salem with Georgie’s grandmother, complete with room for experiments. The agreement was that he would continue to help and support student Georgie.

Mabel was an intelligent and attractive woman. She was much younger than Alexander, but Alexander fell in love with her. The couple would later marry.

Alexander Graham Bell’s phone

From 1874, Alexander Graham Bell ‘s experiments gained momentum and his work on the harmonic telegraph entered the formative phase. Progress was made in both his new laboratory and his parental home. For example, he experimented image with a phonautograph, a kind of pen-like machine that could draw shapes of sound waves on smoked glass.

Bell thought it might be possible to generate undulating electrical currents that corresponded to sound waves. He also believed that multiple metal reeds tuned to a frequency, such as on a harp, could turn undulating waves back into sound. He didn’t have a working prototype at the time.

Telegraph traffic increased rapidly at that time. Orton contracted with inventors Thomas Edison and Elisha Gray to establish a way to transmit multiple telegraph messages on a telegraph line. This was aimed at reducing costs.

A chance encounter between electrical engineer Thomas Watson and Alexander Graham Bell gave him new hope of inventing a working prototype. With financial backing from Sanders and Hubbard, Alexander hired Thomas Watson as his assistant.

Together the couple experimented with acoustic telegraphy. By chance, Watson strummed one of the reeds, and Bell heard the overtones of the reed at the receiving end of the string. These overtones are necessary for the transmission of speech. The couple then concluded that only 1 reed was needed, and not several as they previously thought.

Race to the patent office

Meanwhile, Elisha Gray also experimented with acoustic telegraphy. He invented a way to transmit speech with a water transmitter. He applied for a patent. That same morning, Alexander Graham Bell ‘s attorney also filed. There is still debate over who arrived first.

Bell’s patent number 174,465 was issued on March 7, 1876 by the US Patent Office. The same day, Bell returned to Boston and resumed work. On March 10, 1876, Bell managed to get the telephone working. He uttered the phrase, “Mr. Watson, come here,” through the liquid transmitter. Watson, on the other end of the line, heard this sentence loud and clear.

Alexander Graham Bell was still accused of stealing Gray’s draft. But Alexander Graham Bell did not use Gray’s design until after Gray’s patent was issued for proving his method.

Fast forward to January, 1915, the same two men – Bell and Watson – talked by telephone to each other over a 3400-mile wire between New York and San Francisco, which was the first ceremonial transcontinental telephone call.

Family Life of Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Bell and his former student Mabel Hubbard married on July 11, 1877, a few days after the foundation of the Alexander Bell Telephone Company in 1877, where he was CEO. Together they had four children: Elsie May Bell, Marian Hubbard Bell, Edward Bell, and Robert Bell. The latter two died in infancy. The couple lived in Nova Scotia, on the Beinn Bhreagh estate.

In 1915, the first transcontinental telephone conversation took place, again between Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Watson.

Alexander Bell died of complications from diabetes on August 2, 1922, at his private estate in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. He was 75 years old.

Famous quotes by Alexander Graham Bell

- “Concentrate all your thoughts upon the work at hand. The sun’s rays do not burn until brought to a focus.”

- “Before anything else, preparation is the key to success.”

- “When one door closes, another opens; but we often look so long and so regretfully upon the closed door that we do not see the one which has opened for us.”

- “Great discoveries and improvements invariably involve the cooperation of many minds. I may be given credit for having blazed the trail, but when I look at the subsequent developments I feel the credit is due to others rather than to myself.”

- “Sometimes we stare so long at a door that is closing that we see too late the one that is open.”

- “What this power is I cannot say; all I know is that it exists and it becomes available only when a man is in that state of mind in which he knows exactly what he wants and is fully determined not to quit until he finds it.”

- “Educate the masses, elevate their standard of intelligence, and you will certainly have a successful nation.”

- “A man, as a general rule, owes very little to what he is born with – a man is what he makes of himself.”

- “Dumbness comes from the fact that a child is born deaf and that it consequently never learns how to articulate, for it is by the medium of hearing that such instruction is acquired.”

- “America is a country of inventors, and the greatest of inventors are the newspaper men.”

- “Dumbness comes from the fact that a child is born deaf and that it consequently never learns how to articulate, for it is by the medium of hearing that such instruction is acquired.”

- “The most successful men in the end are those whose success is the result of steady accretion.”

- “I do not recognize the right of the public to break in the front door of a man’s private life in order to satisfy the gaze of the curious… I do not think it right to dissect living men even for the advancement of science. So far as I am concerned, I prefer a post mortem examination to vivisection without anesthetics.”

- “In this experiment, made on the 9th of October, 1876, actual conversation, backwards and forwards, upon the same line, and by the same instruments reciprocally used, was successfully carried on for the first time upon a real line of miles in length.”

- “From my earliest childhood, my attention was specially directed to the subject of acoustics, and specially to the subject of speech, and I was urged by my father to study everything relating to these subjects, as they would have an important bearing upon what was to be my professional work.”

- “A man’s own judgment should be the final appeal in all that relates to himself.”

- “The nation that secures control of the air will ultimately control the world.”

- “I would impress upon your minds the fact that if you want to do a man justice, you should believe what a man says himself rather than what people say he says.”

- “Morse conquered his electrical difficulties although he was only a painter, and I don’t intend to give in either till all is completed.”

- “It is a neck-and-neck race between Mr. Gray and myself who shall complete our apparatus first. He has the advantage over me in being a practical electrician – but I have reason to believe that I am better acquainted with the phenomena of sound than he is – so that I have an advantage there.”

- “It is not, of course, complete yet – but some sentences were understood this afternoon… I feel that I have at last struck the solution of a great problem – and the day is coming when telegraph wires will be laid onto houses just like water or gas – and friends converse with each other without leaving home.”

- “Neither the Army nor the Navy is of any protection, or very little protection, against aerial raids.”

- “I have discovered that my interest in my dear pupil, Mabel, has ripened into a far deeper feeling than that of mere friendship. In fact, I know that I have learned to love her very sincerely.”

- “My knowledge of electrical subjects was not acquired in a methodical manner but was picked up from such books as I could get hold of and from such experiments as I could make with my own hands.”

- “It is hardly an exaggeration to say that oral teachers and sign teachers found it difficult to sit down in the same room without quarreling, and there was intolerance upon both sides. To say ‘oral method’ to a sign teacher was like waving a red flag in the face of a bull, and to say ‘sign language’ to an oralist aroused the deepest resentment.”

- “Such a chimerical idea as telegraphing vocal sounds would indeed, to most minds, seem scarcely feasible enough to spend time in working over. I believe, however, that it is feasible and that I have got the cue to the solution of the problem.”

- “My knowledge of electrical subjects was not acquired in a methodical manner but was picked up from such books as I could get hold of and from such experiments as I could make with my own hands.”

- “Man is the result of slow growth; that is why he occupies the position he does in animal life. What does a pup amount to that has gained its growth in a few days or weeks, beside a man who only attains it in as many years.”

- “Don’t keep forever on the public road, going only where others have gone, and following one after the other like a flock of sheep. Leave the beaten track occasionally and dive into the woods. ‘Every time you do so you will be certain to find something that you have never seen before. Of course it will be a little thing, but do not ignore it. Follow it up, explore all around it; one discovery will lead to another, and before you know it you will have something worth thinking about to occupy your mind. All really big discoveries are the results of thought.”

- “Mr. Watson — Come here — I want to see you.” [First intelligible words spoken over the telephone]

- “Concentrate all your thoughts on the task at hand. The sun’s rays do not burn until brought to a focus.”

- “Leave the beaten track behind occasionally and dive into the woods. Every time you do, you will be certain to find something you have never seen before.”

Books and publications

- 1974. Teacher of the Deaf. Northampton, MA: Clarke School for the Deaf.

- 1969. Memoir Upon the Formation of a Deaf Variety of the Human Race.

- 1920. Is Race Suicide Possible?. Journal of Heredity, 11(8), 339-341.

- 1918. The duration of life and conditions associated with longevity: a study of the Hyde genealogy. Genealogical Record Office.

- 1914. How to Improve the Race: Success Possible, but not by Processes Employed with Lower Animals—Little Gain from Preventing Marriage of Undesirables—Important Point Is Formation of a Prepotent, Desirable Stock by Marriages of Desirable People with Each Other—This Prepotent Stock Will Then Raise the Level of the Great Bulk of Normals. Journal of Heredity, 5(1), 1-7.

- 1912. Sheep-breeding experiments on Beinn Bhreagh. Science, 36(925), 378-384.

- 1908. A few thoughts concerning eugenics. Journal of Heredity, (1), 208-214.

- 1906. The Mechanism of Speech: Lectures Delivered Before the American Association to Promote the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf: to which is Appended a Paper Vowel Theories, Read Before the National Academy of Arts and Sciences. Funk & Wagnalls.

- 1904. The multi-nippled sheep of Beinn Bhreagh. Science, 19(489), 767-768.

- 1903. The tetrahedral principle in kite structure. Judd & Detweiler.

- 1891. Marriage an Address to the Deaf. Gibson Bros.

- 1889. Reading as a Means of Teaching Language to the Deaf. Science, (329), 402-404.

- 1884. Upon the formation of a deaf variety of the human race. US Government Printing Office.

- 1884. Fallacies concerning the deaf. American Annals of the Deaf and Dumb, 29(1), 32-69.

- 1883. Upon a method of teaching language to a very young congenitally deaf child. American annals of the deaf and dumb, 28(2), 124-139.

- 1881. Upon the production of sound by radiant energy. Gibson Brothers, printers.

- 1880. The photophone. Science, (11), 130-134.

- 1880. On the production and reproduction of sound by light. American journal of science, 3(118), 305-324.

How to cite this article:

Janse, B. (2023). Alexander Graham Bell. Retrieved [insert date] from Toolshero: https://www.toolshero.com/toolsheroes/alexander-graham-bell/

Published on: 03/08/2023 | Last update: 12/28/2023

Add a link to this page on your website:

<a href=”https://www.toolshero.com/toolsheroes/alexander-graham-bell/”>Toolshero: Alexander Graham Bell</a>